Bears I Have Met--and Others, by Allen Kelly

CHAPTER I.

THE CALIFORNIA GRIZZLY.

The California Grizzly made his reputation as a man-killer in the days

of the muzzle-loading rifle, when failure to stop him with one shot

deprived the hunter of all advantage in respect of weapons and reversed

their positions instantly, the bear becoming the hunter and the man the

game. In early days, also the Grizzly had no fear of man and took no

pains to keep out of his way, and bears were so numerous that chance

meetings at close quarters were frequent.

But with all of his ferocity when attacked and his formidable strength,

the Grizzly's resentment was often transitory, and many men owe their

lives to his singular lack of persistency in wreaking his wrath upon a

fallen foe. Generalizations on the conduct of animals, other than in

the matter of habits of life governed by what we call instinct, are

likely to be misleading, and when applied to animals of high

intelligence and well-developed individuality, are utterly valueless.

I have found the Grizzly more intelligent than other American bears and

his individual characteristics more marked and varied, and therefore am

disinclined to formulate or accept any rules of conduct for him under

given circumstances. No man can say what a Grizzly will or will not

do, when molested or encountered, any more than he can lay down a

general rule for dogs or men. One bear may display extreme timidity

and run away bawling when wounded, and another may be aggressive enough

to begin hostilities at sight and fight to the death. It can be said

safely, however, that the Grizzly is a far more dangerous animal than

the Black Bear and much more likely to accept a challenge than to run

away.

Want of persistent vindictiveness may not be a general trait of the

species, but it has been shown in so many cases that it is at least a

quite common characteristic. Possibly it is a trait of all bears and

the basis of the almost universal belief that a bear will not molest a

dead man, and that by "playing 'possum" a person attacked by a bear may

evade further injury. That belief or theory has been held from the

earliest times, and it is by no means certain that it is a mere idle

tale or bit of nursery lore. Aesop uses it in one of his fables. Two

men are assailed by a bear, and one climbs a tree while the other

throws himself upon the ground and feigns death. The bear sniffs at

the man on the ground, who holds his breath, concludes that the man is

dead, and goes away. The man who climbed the tree rejoins his

companion, and having seen the bear sniffing at his head, asks him

facetiously what the bear said to him. The man who played 'possum

replies that the bear told him to beware of keeping company with those

who in time of danger leave their friends in the lurch.

This I do know, that bears often invade camps in search of food and

refrain from molesting men asleep or pretending to be asleep. Upon one

occasion a Grizzly of very bad reputation and much feared by residents

in his district, came into my camp on a pitch dark night, and as it

would have been futile to attempt to draw a bead on him and a fight

would have endangered two members of the party who were incapable of

defending themselves, I cautioned everyone to feign sleep and not to

show signs of life if the bear sniffed in their faces. The injunction

was obeyed, the bear satisfied his curiosity, helped himself to food

and went away without molesting anybody.

And that is not an isolated instance. One night a Grizzly invaded a

bivouac, undeterred by the still blazing fire, and tried to reach a

haunch of venison hung upon a limb directly over one of the party. The

man--Saml Snedden, the first settler in Lockwood Valley, Cal.--awoke

and saw the great beast towering over him and stretching up in a vain

effort to reach the venison, and he greatly feared that in coming down

to all fours again the bear might forget his presence and step upon

him. Snedden tried furtively to draw his rifle out from the blankets

in which he had enveloped it, but found that he could not get the

weapon, without attracting the bear's attention and probably provoking

immediate attack. So he abandoned the attempt, kept perfectly still

and watched the bear with half-closed eyes. The Grizzly realized that

the meat was beyond his reach, and with a sighing grunt came down to

all fours, stepping upon and crushing flat a tin cup filled with water

within a foot of the man's head. The bear inquisitively turned the

crushed cup over, smelt of it, sniffed at Snedden's ear and slouched

slowly away into the darkness as noiselessly as a phantom, and only one

man in the camp knew he had been there except by the sign of his

footprints and the flattened cup.

Many hunters have told me of similar experiences, and never have I

heard of one instance of unprovoked attack upon a sleeping person by a

bear, or for that matter by any other of the large carnivorae of this

country. Only one authentic instance of a bear feeding on human flesh

have I known, and that was under unusual circumstances.

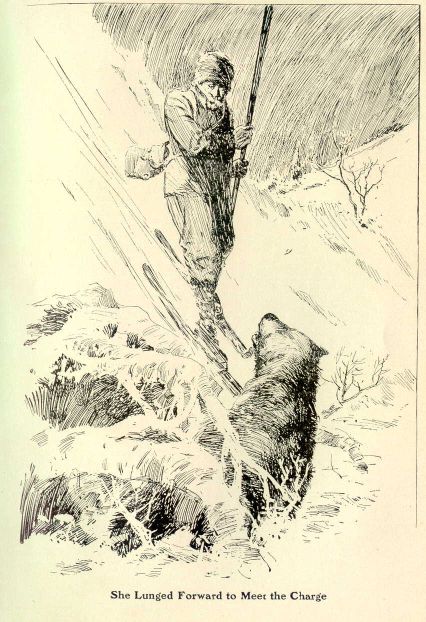

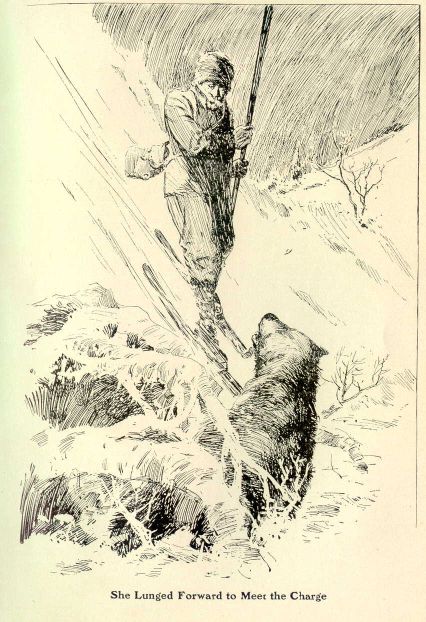

Two things will be noted by the reader of these accounts of California

bear fights: First, that the Grizzly's point of attack is usually the

face or head, and second, that, except in the case of she-bears

protecting or avenging their cubs, the Grizzly ceased his attack when

satisfied that his enemy was no longer capable of continuing the fight,

and showed no disposition to wantonly mangle an apparently dead man.

Since the forty she-bears came out of the wilderness and ate up a drove

of small boys for guying a holy man, who was unduly sensitive about his

personal dignity, the female of the ursine species, however, has been

notorious for ill-temper and vindictive pertinacity, and she maintains

that reputation to this day.

In the summer of 1850, G. W. Applegate and his brother John were mining

at Horse Shoe Bar on the American River. The nearest base of supplies

at that time was Georgetown, eighteen miles distant by trail. One

evening in early summer, having run short of provisions, George and his

brother started to walk to that camp to make purchases. Darkness soon

overtook them and while descending into Canyon Creek they heard a bear

snort at some distance behind. In a few moments they heard it again,

louder than before, and John rather anxiously remarked that he thought

the bear was following them. George thought not, but in a few seconds

after crossing the stream and beginning the ascent upon the other side,

both distinctly heard him come--splash, splash, splash--through the

water directly upon their trail.

It was as dark as Erebus, and they were without weapons larger than

pocket knives--a serious position with an angry Grizzly dogging their

steps. Their first thought was to climb a tree, but knowing they were

not far from the cabin of a man named Work, they took to their heels

and did their best running to reach that haven of refuge ahead of their

formidable follower. They reached the cabin, rushed in, slammed and

fastened the door behind them, and with breathless intervals gasped out

their tale. Work kept a bar for the sale of whiskey, and he and his

son, a stout young man, with two or three miners, were sitting on rude

seats around a whiskey barrel playing cards when the two frightened men

rushed in.

The cabin was built by planting posts firmly in the ground at a

distance of some three feet apart, and in the form of a parallelogram,

then nailing shakes upon these posts and on the roof. The sides were

held together by cross beams, connecting the tops of the opposite

posts. There was one rude window, made by cutting a hole in the side

of the wall about four feet from the ground and covering this with

greased paper, glass being an unattainable luxury. Notwithstanding the

belief that there was not a man in those days but wore a red shirt and

a big revolver, there was not a firearm in the place.

In a few seconds the bear was heard angrily sniffing at the door, and

an instant later his powerful paw came tearing through the frail shakes

and he poked his head and neck through the opening and gravely surveyed

the terrified party. Every man sprang upon the bar and thence to the

cross beam with the alacrity given only by terror. After sniffing a

moment and calmly gazing around the room and up at the frightened men,

the bear quietly withdrew his head and retired.

After an interval of quiet, the men ventured down and were eagerly

discussing the event, when the bear again made its presence known by

rearing up and thrusting its head through the paper of the window.

Upon this occasion some of the men stood their ground, and young Work,

seizing an iron-pointed Jacob's staff, ran full tilt at the bear, and

thrust it deeply into its chest. The bear again disappeared, taking

the Jacob's staff, and appeared no more that night.

The following morning, search being made, the bear was found dead some

yards from the cabin, with the staff thrust through the heart. It

proved to be a female and was severely wounded in several places with

rifle balls.

Subsequent inquiries elicited the fact that on the previous day a party

of hunters from Georgetown had captured two cubs and wounded the

mother, which had escaped. This was evidently the same bear in search

of her cubs.

* * * * *

In the spring of the year, somewhere early in the fifties, a party of

five left the mining camp of Coloma for the purpose of hunting deer for

the market in the locality of Mosquito Canyon. On the morning of the

second day in camp the party separated, each going his own way to hunt,

and at night it was found that one of their members named Broadus

failed to appear. The others started out in different directions to

search for him the next morning, and after a day spent in fruitless

searching, they returned to camp only to find that another of their

number, named William Jabine, was this night missing.

After an anxious night, chiefly spent in discussing the probable fate

of their missing companions, the remaining three started out on the

trail of Jabine, he having told them the previous morning what part of

the country he was going to travel. Slowly following his tracks left

in the soft soil and broken down herbage, they found him about noon,

terribly mangled and unconscious, but alive. The flesh on his face was

torn and lacerated in a frightful manner, and he was otherwise injured

in his chest and body.

Further search revealed, near by, the dead body of their other missing

comrade, seated on a bowlder by the side of a small stream with his

head on his folded arms, which were supported by a shelf of rock in

front of him. His whole under jaw had been bitten off and torn away,

and a large pool of clotted blood at his feet showed that he had slowly

bled to death after having been attacked and wounded by a bear. The

ground showed evidences of a fearful struggle, being torn up and

liberally sprinkled with blood for yards around.

The men carried Jabine to the nearest mining camp, whence others went

to bring in the body of Broadus.

Jabine finally recovered, but he was shockingly disfigured for life.

He afterwards told how he came upon the tracks of Broadus, and on

reaching the spot where Broadus had received his death wound, he was

suddenly attacked by a huge she-bear that was followed by two small

cubs. The bear had evidently been severely wounded by Broadus and was

in a terrible rage. She seized Jabine before he could turn to flee,

and falling with her whole weight upon his body and chest, began biting

his face. He soon lost consciousness from the pressure upon his chest,

and remembered no more.

The poor fellow became a misanthrope, owing to his terrible

disfigurement, and was finally found drowned in the river near Coloma.

In 1850 a number of miners were camped upon the spot where the little

town of Todd's Valley now stands. Among them were three brothers named

Gaylord, who had just arrived from Illinois. These young men used to

help out the proceeds of their claim by an occasional hunt, taking

their venison down to the river when killed, where a carcass was

readily disposed of for two ounces.

One evening when the sun was about an hour high, one of the brothers

took his rifle and went out upon the hills and did not return that

night. The following morning his two brothers set out in search and

soon found him dead, bitten through the spine in the neck, evidently by

a bear. His rifle was unloaded and the tracks showed where he had

fled, pursued by the angry animal, been overtaken, and killed.

On the succeeding day a hunt was organized and some twenty men turned

out to seek revenge. The bears, for there were two of them, were

tracked into a deep rocky canyon running from Forest Hill to Big Bar.

Large rocks were rolled down its sides, and the bears were routed out

and both killed.

In 1851, three men armed with Kentucky rifles, which were not only

muzzle-loaders, but of small calibre and less effective than the

ordinary .32 calibre rifle of to-day, were hunting deer on the divide

between Volcano and Shirttail Canyons in Placer county. In the heavy

timber on the slope they encountered a large Grizzly coming up out of

Volcano Canyon. The bear was a hundred yards distant when they saw him

and evinced no desire for trouble, and two of the hunters were more

than willing to give him the trail and let him go about his business in

peace. The other, a man named Wright, who had killed small bears, but

knew nothing about the Grizzly, insisted on attacking, and prepared to

shoot. The others assured him that a bullet from a Kentucky rifle at

that distance would only provoke the bear to rush them, and begged him

not to fire. But Wright laughed at them and pulled trigger with a bead

on the bear's side, where even a heavy ball would be wasted.

The Grizzly reared upon his haunches, bit at the place where the ball

stung him, and after waving his paws in the air two or three times,

came directly for Wright with a fierce growl. The party all took to

their heels and separated, but the bear soon overtook Wright and with

one blow of his paw struck the man, face downward, upon the snow and

began biting him about the head, back and arms. The other hunters,

seeing the desperate case of their companion, rushed up and fired at

the bear at close range, fortunately killing him with a bullet in the

base of the brain.

Wright, on being relieved of the weight of his antagonist, sat up in a

dazed condition, with the blood pouring in streams down his face. He

had received several severe bites in the back and arms, but the worst

wound was on the head, where the bear had struck him with his claws.

His scalp was almost torn from his head, and a large piece of skull

some three inches in diameter was broken out and lifted from the brain

as cleanly as if done by the surgeon's trephine.

Strange to say, Wright complained of but little pain, excepting from a

bite in the arm, and soon recovered his senses. His comrades replaced

the mangled scalp, and bleeding soon ceased. A fire was built to keep

him warm and while one watched with the wounded man the other returned

to the trail to intercept a pack train. On the arrival of the mules,

Wright was helped upon one of their backs, and rode unaided to the

Baker ranch.

A surgeon was sent for from Greenwood Valley, who, on his arrival,

removed the loose piece of bone from the skull and dressed the wounds.

The membranes of the brain were uninjured, and the man quickly

recovered, but of course had a dangerous hole in his skull that

incapacitated him for work. One Sunday, some weeks afterward, the

miners held a meeting, subscribed several hundred dollars and sent

Wright home to his friends in Boston.

* * * * *

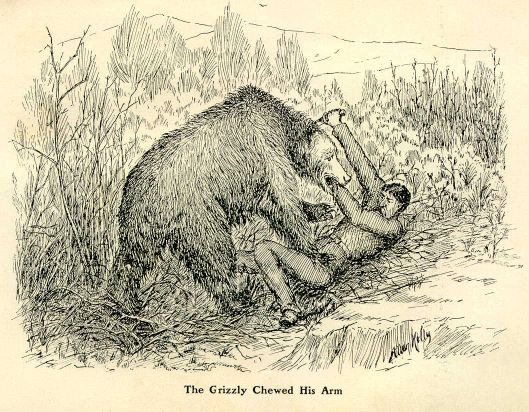

Mike Brannan was a miner on the Piru River in Southern California. The

river, or creek, runs through a rough mountain district, and Brannan's

claim was in the wildest part of it. He and his partner met a Grizzly

on the trail, and Brannan had no better judgment than to fire his

revolver at the bear instead of getting out of the way. The Grizzly

charged, smashed the partner's skull with a blow and tumbled Brannan

over a bank.

Brannan was stunned by the fall, and when consciousness returned he saw

the bear standing across his body, watching him intently for signs of

life. He tried to keep perfectly still and hold his breath, but the

suspense was too great a strain and involuntarily he moved the fingers

of his right hand. The bear did not see the movement, and when Brannan

realized that his fingers had just touched his revolver, he conceived

the desperate idea that he could reach the weapon and use it quickly

enough to blow a hole through the bear's head and save himself from the

attack which he felt he could not avert much longer by shamming.

To grasp the revolver it was necessary to stretch his arm full length,

and he tried to do that slowly and imperceptibly, but his anxiety

overcame his prudence and he made a movement that the watchful Grizzly

detected. Instantly the bear pinned the arm with one paw, placed the

other upon Brannan's breast and with his teeth tore out the biceps

muscle. Brannan had the good luck to faint at that moment, and when

his senses again returned he was alone. The Grizzly had watched him

until satisfied that there was no more harm in him, and then left him.

Brannan managed to get to his cabin and eventually recovered, only to

be murdered some years later for the gold dust he had stored away.

NOTE.--For many of the facts in this chapter of adventures with

grizzlies in Placer and El Dorado counties in 1850 and 1851, I am

indebted to Dr. R. F. Rooney, of Auburn, Cal., who obtained the details

at first hand from pioneers.--A. K.

Home

>

General Discussion

>

Topic

CHAPTER XXII. A DENFUL OF GRIZZLIES

All posts are those of the individual authors and the owner

of this site does not endorse them. Content should be considered opinion

and not fact until verified independently.

April 24, 2009 04:39PM | Admin Registered: 16 years ago Posts: 17,152 |

April 24, 2009 05:59PM | Admin Registered: 16 years ago Posts: 17,152 |

CHAPTER II.

THE STORY OF MONARCH.

Early in 1889, the editor of a San Francisco newspaper sent me out to

catch a Grizzly. He wanted to present to the city a good specimen of

the big California bear, partly because he believed the species was

almost extinct, and mainly because the exploit would be unique in

journalism and attract attention to his paper. Efforts to obtain a

Grizzly by purchase and "fake" a story of his capture had proved

fruitless for the sufficient reason that no captive Grizzly of the true

California type could be found, and the enterprising journal was

constrained to resort to the prosaic expedient of laying a foundation

of fact and veritable achievement for its self-advertising.

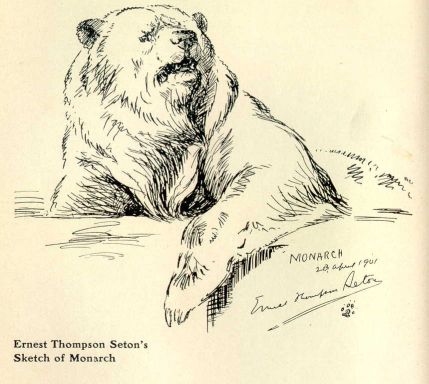

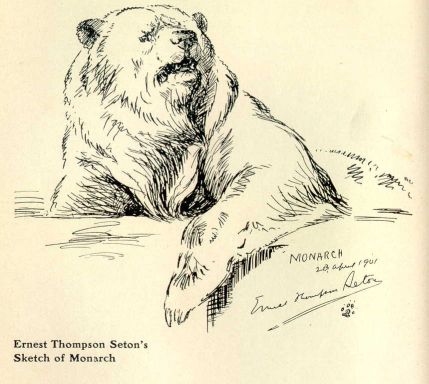

Ernest Thompson Seton's Sketch of Monarch

The assignment was given to me because I was the only man on the paper

who was supposed to know anything about bears. Such knowledge as I

had, and it was not very extensive, had been acquired on hunting trips,

some successful and more otherwise, in the Sierra Nevada and Cascades.

I had had no experience in trapping, but I accepted the assignment with

entire confidence and great joy over the chance to get into the

mountains for a long outing. The outing proved to be much longer than

the editor expected, and trapping a bear quite a different matter from

killing one.

From Santa Paula, I struck into the mountains of Ventura county with an

outfit largely composed of information, advice and over-paid

assistance. The first two months of the trip were consumed in

developing the inaccuracy of most of the information and the utter

worthlessness of all the advice and costly assistance, and in acquiring

some rudimentary knowledge of the habits of bears and the art of

trapping them. Traps were built, under advice, where there was not one

chance in a thousand of catching anything, and bogus bear-tracks, made

with a neatly-executed model by an ingenious guide, who preferred

loafing about camp to moving it, kept the expedition from seeking more

promising country.

The editor became tired of waiting for his big sensation and ordered me

home. I respectfully but firmly refused to go home bearless, and the

editor fired me by wire. I fired the ingenious but sedentary

assistant, discarded all the advice that had been unloaded upon me by

the able bear-liars of Ventura, reduced my impedimenta to what one

lone, lorn burro could pack, broke camp and struck for a better Grizzly

pasture, determined to play the string out alone and in my own way.

The place I selected for further operations was the regular beat of old

Pinto, a Grizzly that had been killing cattle on Gen. Beale's range in

the mountains west of Tehachepi and above Antelope Valley.

Old Pinto was no myth, and he didn't make tracks with a whittled pine

foot. His lair was a dense manzanita thicket upon the slope of a

limestone ridge about a mile from the spring by which I camped, and he

roamed all over the neighborhood. In soft ground he made a track

fourteen inches long and nine inches wide, but although at the time I

took that for the size of his foot, I am now inclined to think that it

was the combined track of front and hind foot, the hind foot

"over-tracking" a few inches, obliterating the claw marks of the front

foot and increasing the size of the imprint both in length and width.

Nevertheless he was a very large bear, and he loomed up formidably in

the dusk of an evening when I saw him feasting, forty yards away, upon

a big steer he had killed.

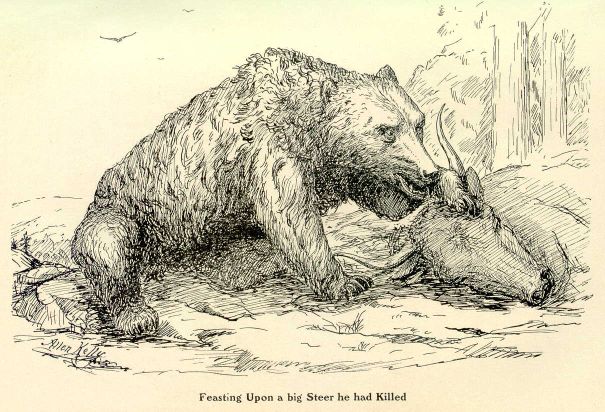

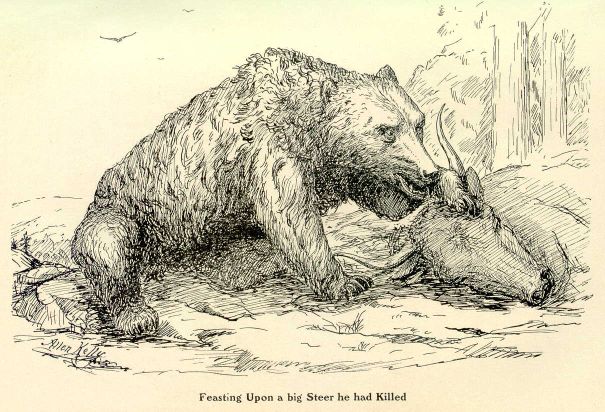

Feasting upon a big steer he had killed

Pinto had the reputation of being not only dangerous but malevolent,

and there were oft told tales of domiciliary visits paid by him at the

cabins of settlers, and of aggressive advances upon mounted vaqueros,

who were saved by the speed of their horses. Doubtless the bear was

audacious in foraging and indifferent to the presence of man, but he

was not malevolent. Indeed, I have yet to hear on any credible

authority of a malevolent bear, or, for that matter, any other wild

animal in North America whose disposition and habit is to seek trouble

with man and go out of its way with the deliberate purpose of attacking

him. For many weeks I camped by that spring, much of the time alone,

and without even a dog, with only a blanket for covering and the

heavens for a roof, and my sleep never was disturbed by anything larger

than a wood rat. My camp was on one of Pinto's beaten trails, but he

abandoned it and passed fifty yards to one side or the other whenever

his business took him down that way, and he never meddled with me or

mine. One night, as his tracks showed, he came to within twenty feet

of my bivouac, sniffed around inquiringly and passed on.

I built two stout traps for Pinto's benefit, and day after day I

dragged bait around and through the manzanita thickets on the ridge and

over all his trails, and sometimes I found tracks so fresh that I was

satisfied he had heard me coming and had turned aside. There were

cougar and lynx tracks all over the mountains, but I seldom saw the

animals and then only got fleeting glimpses of them as they fled out of

my way.

Many of my prejudices and all my story-book notions about the behavior

of the carnivorae were discredited by experience, and I was forced to

recognize the plain truth that the only mischievous animal, the only

creature meditating and planning evil on that mountain--excepting of

course the evil incident to the procurement of food--was a man with a

gun. I was the only really dangerous and unnecessarily destructive

animal in the woods, and all the rest were afraid of me.

After a time, because I had no intention of killing Pinto if I should

meet him, I quit carrying a rifle, except when I wanted venison, and

tramped all over the mountain in daylight or in darkness without giving

much thought to possible encounters. True, I carried a revolver, but

that was force of habit mainly, and a six-shooter is company of a sort

to a man in the wilderness even if he does not expect to need it. When

one has "packed a gun" for years, he feels uncomfortable without it;

not because he thinks he has any use for it, but because it has become

a part of his attire and its absence unconsciously frets him and sets

him wondering vaguely if he has lost his suspenders or forgotten to put

on a tie.

That the big Grizzly was not quite so audacious and adventurous as he

was reputed to be was demonstrated by his suspicious avoidance of the

traps while they were new to him, and it became evident that he could

not be inveigled into them even by meat and honey until they should

become familiar objects to him and he should get accustomed to my scent

upon his trails. That I would have caught old Pinto in time there is

no doubt, for eventually he was caught in each of the traps, although

he escaped through the carelessness of the man who baited and set them.

The traps were tight pens, built of large oak logs notched and pinned,

roofed and floored with heavy logs and fitted with falling doors of

four-inch plank. They were stout enough, and when I saw them ten years

later they were sound and fit to hold anything that wears fur, although

old Pinto had clawed all the bark off the logs and left deep furrows in

them.

As a matter of course, all the hunters and mountain men for fifty miles

around knew that I was trying to catch a Grizzly, and some of them

built traps on their own hook, hoping to catch a bear and make a few

dollars. I had encouraged them by promising to pay well for his

trouble anybody who should get a bear in his own trap, or find one in

any of the numerous traps I had built and send me word.

Late in October, I heard that a bear had got into a trap on Gleason

Mountain, and leaving Pinto to his own devices, I went over to look at

the captive. The Mexican acting as jailor did not know me, and I

discovered that Allen Kelly was supposed to be the agent of a

millionaire and an "easy mark," who would pay a fabulous sum for a

bear. The Mexican assured me that he was about to get wealth beyond

the dreams of avarice for that bear from a San Francisco man, meaning

said Kelly, whereupon I congratulated him, disparaged the bear and

turned to go. The Mexican followed me down the trail and began

complaining that the alleged purchaser of the bear was dilatory in

closing the deal with cash. He, Mateo, was aggrieved by this

unbusinesslike behavior, and it would be no more than proper for him to

resent it and teach the man a lesson in commercial manners by selling

the bear to somebody else, even to me, for instance. Mateo's haste to

get that bear off his hands was evident, but the reason for it was not

apparent. Later I understood.

Monarch had the bad luck to get into a trap built by a little syndicate

of which Mateo was a member. Mateo watched the trap, while the others

supplied beef for bait. They were to divide the large sum which they

expected to get from me in case they caught a bear before I did, and

very likely my fired assistant had a contingent interest in the

enterprise. Mateo was the only member of the syndicate on deck when I

arrived, and deeming a bird in his hand worth a whole flock in the

syndicate bush, he made the best bargain he could and left the others

to whistle for dividends. Ten years afterward I met the cattleman who

furnished the capital and the beef, and from his strenuous remarks

about his Mexican partner I inferred that the syndicate had been deeply

disappointed. I also learned for the first time why Mateo was so

anxious for me to take the bear off his hands when the evident original

purpose was to held me up for a good round sum. The hold-up would have

failed, however, because I had spent more than $1,200 and lost five

months' time, was nearly broke, did not represent anybody but myself at

that stage of my bear-catching career, and for all I knew the editor

might have changed his mind about wanting a Grizzly at any price.

Finally I consented to take the bear and struck a bargain, and not

until money had passed and a receipt was to be signed did Mateo know

with whom he was dealing. He paid me the dubious compliment of

muttering that I was "un coyote," and as that animal is the B'rer

Rabbit of Mexican folk lore, I inferred that the excellent Mateo

intended to express admiration for the only evidence of business

capacity to be found in my entire career. That dicker for a bear

stands out as the sole trade I ever made in which I was not

unmistakably and comprehensively "stuck." Mateo was more than repaid

for his trouble, however. He helped me build a box, and get the bear

into it, and I took Monarch to San Francisco and sold him to the editor

of the enterprising paper, who eventually gave him to Golden Gate Park.

The newspaper account of the capture of Monarch was elaborated to suit

the exigencies of enterprising journalism, picturesque features were

introduced where the editorial judgment dictated, and mere facts, such

as the name of the county in which the bear was caught, fell under the

ban of a careless blue pencil and were distorted beyond recognition.

More than one-fourth of Joaquin Miller's "True Bear Stories"' consists

of that newspaper yarn, copied verbatim and without amendment, revision

or verification. The other three-fourths of the book, it is to be

hoped, is at least equally true.

Considering all the frills of fiction that were put into the story to

make it readable, the careless inaccuracies that were edited into it,

and the fact that many persons knew of the preliminary attempts to buy

any old bear and fake a capture, it is not strange that people who

always know the "inside history" of everything that happens, wag their

heads wisely and declare that Monarch was obtained from a bankrupt

circus, or is an ex-dancer of the streets sold to the newspaper by a

hard-up Italian.

But it is incredible that any one who knows a bear from a Berkshire hog

could for an instant mistake Monarch for any variety of tamable bear or

imagine that any man ever had the hardihood to give him dancing lessons.

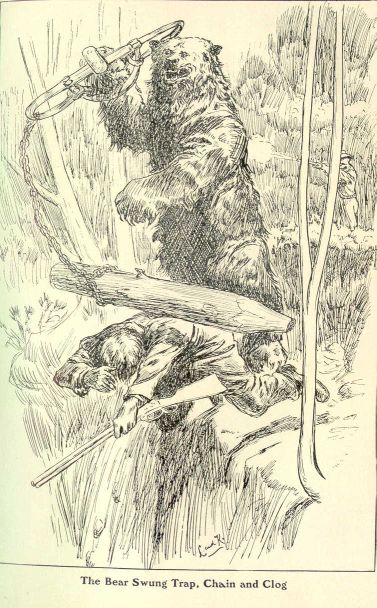

When Monarch found himself caught in the syndicate trap on Gleason

Mountain, he made furious efforts to escape. He bit and tore at the

logs, hurled his great bulk against the sides and tried to enlarge

every chink that admitted light. He required unremitting attention

with a sharpened stake to prevent him from breaking out.

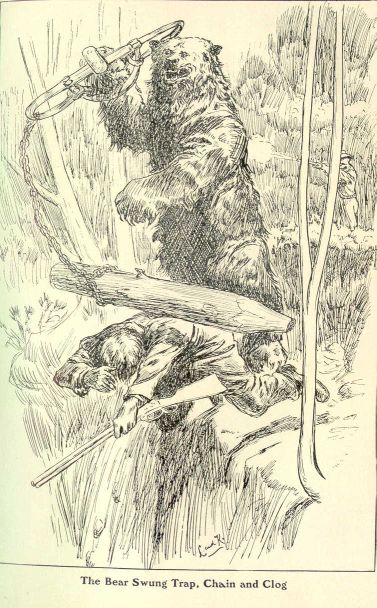

For a full week the Grizzly raged and refused to touch food that was

thrown to him. Then he became exhausted and the task of securing him

and removing him from the trap was begun. The first thing necessary

was to make a chain fast to one of his fore-legs. That job was begun

at eight o'clock in the morning and finished at six o'clock in the

afternoon. Much time was wasted in trying to work with the chain

between two of the side logs. Whenever the bear stepped into the loop

as it lay upon the floor and the chain was drawn tight around his

fore-leg just above the foot, he pulled it off easily with the other

paw, letting the men who held the chain fall over backward. The feat

was finally accomplished by letting the looped chain down between the

roof logs, so that when the bear stepped into it and it was drawn

sharply upward, it caught him well up toward the shoulder.

Having one leg well anchored, it was comparatively easy to introduce

chains and ropes between the side logs and secure his other legs. He

fought furiously during the whole operation, and chewed the chains

until he splintered his canine teeth to the stubs and spattered the

floor of the trap with bloody froth. It was painful to see the plucky

brute hurting himself uselessly, but it could not be helped, as he

would not give up while he could move limb or jaw.

The next operation was gagging the bear so that he could not bite. The

door of the trap was raised and a billet of wood was held where he

could seize it, which he promptly did. A cord made fast to the stick

was quickly wound around his jaws, with turns around the stick on each

side, and passed back of his ears and around his neck like a bridle.

By that means his jaws were firmly bound to the stick in such a manner

that he could not move them, while his mouth was left open for

breathing.

While one man held the bear's head down by pressing with his whole

weight upon the ends of the gag, another went into the trap and put a

chain collar around the Grizzly's neck, securing it in place with a

light chain attached to the collar at the back, passing down under his

armpits and up to his throat, where it was again made fast. The collar

passed through a ring attached by a swivel to the end of a heavy chain

of Norwegian iron. A stout rope was fastened around the bear's loins

also, and to this another strong chain was attached. This done, the

gag was removed and the Grizzly was ready for his journey down the

mountain.

In the morning he was hauled out of the trap and bound down on a rough

skeleton sled made from a forked limb, very much like the contrivance

called by lumbermen a "go-devil." Great difficulty was encountered in

securing a team of horses that could be induced to haul the bear. The

first two teams were so terrified that but little progress could be

made, but the third team was tractable and the trip down the mountain

to the nearest wagon road was finished in four days.

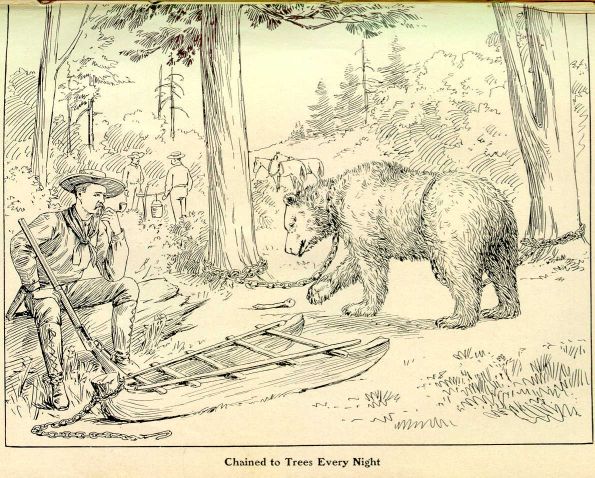

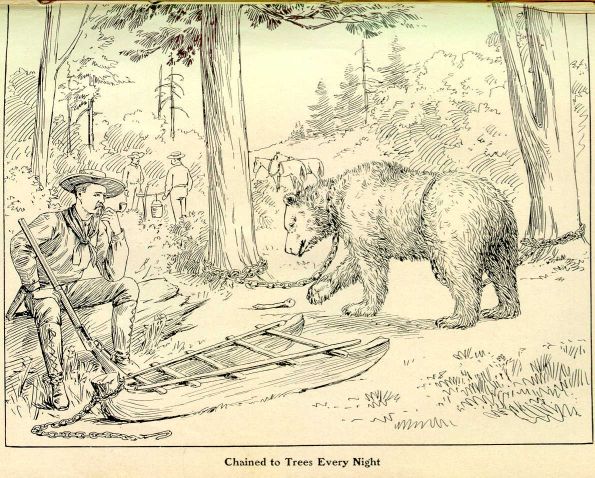

The bear was released from the "go-devil" and chained to trees every

night; and so long as the camp fire burned brightly he would lie still

and watch it attentively, but when the fire burned low he would get up

and restlessly pace to and fro and tug at the chains, stopping now and

then to seize in his arms the tree to which he was anchored and test

its strength by shaking it. Every morning the same old fight had to be

fought before he could be tied to his sled. He became very expert in

dodging ropes and seizing them when the loops fell over his legs, and

considerable strategic skill was required to lasso his paws and stretch

him out. In the beginning of these contests the Grizzly uttered angry

growls, but soon became silent and fought with dogged persistency,

watching every movement of his foes with alert attention and wasting no

energy in aimless struggles. He soon learned to keep his hind feet

well under him and his body close to the ground, which left only his

head and fore-legs to be defended from the ropes. So adroit and quick

was the bear in the use of his paws that a dozen men could not get a

rope on him while he remained in that posture of defence. But when two

or three men grasped the chain that was around his body and suddenly

threw him on his back, all four of his legs were in the air at once,

the riatas flew from all directions and he was vanquished.

Chained to trees every night

Monarch was pretty well worn out when the wagon road was reached, and

doubtless enjoyed the few days of rest and quiet that were allowed him

while a cage was being built for his further transportation. He made

the remainder of the journey to San Francisco by wagon and railroad,

confined in a box constructed of inch-and-a-half Oregon pine that had

an iron grating at one end. The box was not strong enough to have held

him for five minutes had he attacked it as he attacked the trap and as

he subsequently demolished an iron-lined den, but I put my trust in the

moral influence of the chain around his neck. The Grizzly accepted the

situation resignedly and behaved admirably during the whole trip.

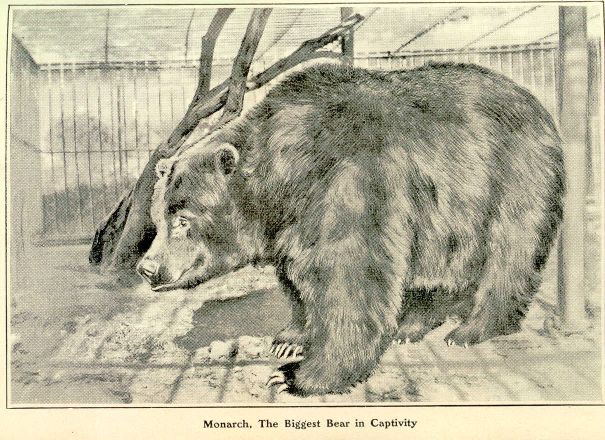

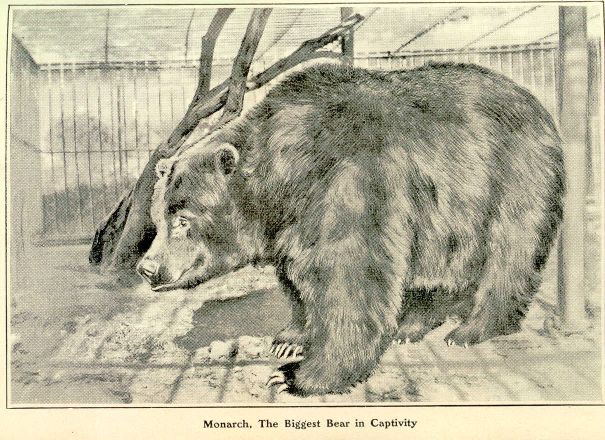

Monarch is the largest bear in captivity and a thoroughbred Californian

Grizzly. No naturalist needs a second glance at him to classify him as

Ursus Horribilis. He stands four feet high at the shoulder, measures

three feet across the chest, 12 inches between the ears and 18 inches

from ear to nose, and his weight is estimated by the best judges at

from 1200 to 1600 pounds. He never has been weighed. In disposition

he is independent and militant. He will fight anything from a crowbar

to a powder magazine, and permit no man to handle him while he can move

a muscle. And yet when he and I were acquainted--I have not seen him

since he was taken to Golden Gate Park--he was not unreasonably

quarrelsome, but preserved an attitude of armed neutrality. He would

accept peace offerings from my hand, taking bits of sugar with care not

to include my fingers, but would tolerate no petting. Within certain

limits he would acknowledge an authority which had been made real to

him by chains and imprisonment, and reluctantly suspend an intended

blow and retreat to a corner when insistently commanded, yet the fires

of rebellion never were extinguished and it would have been foolhardy

to get within effective reach of his paw. To strangers he was

irreconcilable and unapproachable.

Monarch passed three or four years in a steel cell before he was taken

to the Park. He devoted a week or so to trying to get out and testing

every bar and joint of his prison, and when he realized that his

strength was over-matched, he broke down and sobbed. That was the

critical point, and had he not been treated tactfully by Louis Ohnimus,

doubtless the big Grizzly would have died of nervous collapse. A live

fowl was put before him after he had refused food and disdained to

notice efforts to attract his attention, and the old instinct to kill

was aroused in him. His dulled eyes gleamed green, a swift clutching

stroke of the paw secured the fowl. Monarch bolted the dainty morsel,

feathers and all, and his interest in life was renewed with the revival

of his savage propensity to slay.

From that moment he accepted the situation and made the best of it. He

was provided with a bed of shavings, and he soon learned the routine of

his keeper's work in removing the bed. Monarch would not permit the

keeper to remove a single shaving from the cage if a fresh supply was

not in sight. He would gather all the bedding in a pile, lie upon it

and guard every shred jealously, striking and smashing any implement of

wood or iron thrust into the cage to filch his treasure. But when a

sackful of fresh shavings was placed where he could see it, Monarch

voluntarily left his bed, went to another part of the cage and watched

the removal of the pile without interfering.

In intelligence and quickness of comprehension, the Grizzly was

superior to other animals in the zoological garden and compared not

unfavorably with a bright dog. It could not be said of him, as of most

other animals, that man's mastery of him was due to his failure to

realize his own power. He knew his own strength and how to apply it,

and only the superior strength of iron and steel kept him from doing

all the damage of which he was capable.

The lions, for example, were safely kept in cages which they could have

broken with a blow rightly placed. Monarch discovered the weak places

of such a cage within a few hours and wrecked it with swift skill.

When inveigled into a movable cage with a falling door, he turned the

instant the door fell, seized the lower edge and tried to raise it.

When placed in a barred enclosure in the park, he began digging under

the stone foundation of the fence, necessitating the excavation of a

deep trench and the emplacement therein of large boulders to prevent

his escape. Then he tried the aerial route, climbed the twelve foot

iron palings, bent the tops of inch and a half bars and was nearly over

when detected and pushed back.

He remains captive only because it is physically impossible for him to

escape, not because he is in the least unaware of his power or inept in

using it. Apparently he has no illusions concerning man and no respect

for him as a superior being. He has been beaten by superior cunning,

but never conquered, and he gives no parole to refrain from renewing

the contest when opportunity offers.

Mr. Ernest Thompson Seton saw Monarch and sketched him in 1901, and he

said: "I consider him the finest Grizzly I have seen in captivity."

Monarch, The Biggest Bear in Captivity

NOTE.--Without doubt the largest captive grizzly bear in the world, may

be seen in the Golden Gate Park, San Francisco. As to his exact

weight, there is much conjecture. That has not been determined, as the

bear has never been placed on a scale. Good judges estimate it at not

far from twelve hundred pounds. The bear's appearance justifies that

conclusion. Monarch enjoys the enviable distinction of being the

largest captive bear in the world.--N. Y. Tribune, March 8, 1903.

THE STORY OF MONARCH.

Early in 1889, the editor of a San Francisco newspaper sent me out to

catch a Grizzly. He wanted to present to the city a good specimen of

the big California bear, partly because he believed the species was

almost extinct, and mainly because the exploit would be unique in

journalism and attract attention to his paper. Efforts to obtain a

Grizzly by purchase and "fake" a story of his capture had proved

fruitless for the sufficient reason that no captive Grizzly of the true

California type could be found, and the enterprising journal was

constrained to resort to the prosaic expedient of laying a foundation

of fact and veritable achievement for its self-advertising.

Ernest Thompson Seton's Sketch of Monarch

The assignment was given to me because I was the only man on the paper

who was supposed to know anything about bears. Such knowledge as I

had, and it was not very extensive, had been acquired on hunting trips,

some successful and more otherwise, in the Sierra Nevada and Cascades.

I had had no experience in trapping, but I accepted the assignment with

entire confidence and great joy over the chance to get into the

mountains for a long outing. The outing proved to be much longer than

the editor expected, and trapping a bear quite a different matter from

killing one.

From Santa Paula, I struck into the mountains of Ventura county with an

outfit largely composed of information, advice and over-paid

assistance. The first two months of the trip were consumed in

developing the inaccuracy of most of the information and the utter

worthlessness of all the advice and costly assistance, and in acquiring

some rudimentary knowledge of the habits of bears and the art of

trapping them. Traps were built, under advice, where there was not one

chance in a thousand of catching anything, and bogus bear-tracks, made

with a neatly-executed model by an ingenious guide, who preferred

loafing about camp to moving it, kept the expedition from seeking more

promising country.

The editor became tired of waiting for his big sensation and ordered me

home. I respectfully but firmly refused to go home bearless, and the

editor fired me by wire. I fired the ingenious but sedentary

assistant, discarded all the advice that had been unloaded upon me by

the able bear-liars of Ventura, reduced my impedimenta to what one

lone, lorn burro could pack, broke camp and struck for a better Grizzly

pasture, determined to play the string out alone and in my own way.

The place I selected for further operations was the regular beat of old

Pinto, a Grizzly that had been killing cattle on Gen. Beale's range in

the mountains west of Tehachepi and above Antelope Valley.

Old Pinto was no myth, and he didn't make tracks with a whittled pine

foot. His lair was a dense manzanita thicket upon the slope of a

limestone ridge about a mile from the spring by which I camped, and he

roamed all over the neighborhood. In soft ground he made a track

fourteen inches long and nine inches wide, but although at the time I

took that for the size of his foot, I am now inclined to think that it

was the combined track of front and hind foot, the hind foot

"over-tracking" a few inches, obliterating the claw marks of the front

foot and increasing the size of the imprint both in length and width.

Nevertheless he was a very large bear, and he loomed up formidably in

the dusk of an evening when I saw him feasting, forty yards away, upon

a big steer he had killed.

Feasting upon a big steer he had killed

Pinto had the reputation of being not only dangerous but malevolent,

and there were oft told tales of domiciliary visits paid by him at the

cabins of settlers, and of aggressive advances upon mounted vaqueros,

who were saved by the speed of their horses. Doubtless the bear was

audacious in foraging and indifferent to the presence of man, but he

was not malevolent. Indeed, I have yet to hear on any credible

authority of a malevolent bear, or, for that matter, any other wild

animal in North America whose disposition and habit is to seek trouble

with man and go out of its way with the deliberate purpose of attacking

him. For many weeks I camped by that spring, much of the time alone,

and without even a dog, with only a blanket for covering and the

heavens for a roof, and my sleep never was disturbed by anything larger

than a wood rat. My camp was on one of Pinto's beaten trails, but he

abandoned it and passed fifty yards to one side or the other whenever

his business took him down that way, and he never meddled with me or

mine. One night, as his tracks showed, he came to within twenty feet

of my bivouac, sniffed around inquiringly and passed on.

I built two stout traps for Pinto's benefit, and day after day I

dragged bait around and through the manzanita thickets on the ridge and

over all his trails, and sometimes I found tracks so fresh that I was

satisfied he had heard me coming and had turned aside. There were

cougar and lynx tracks all over the mountains, but I seldom saw the

animals and then only got fleeting glimpses of them as they fled out of

my way.

Many of my prejudices and all my story-book notions about the behavior

of the carnivorae were discredited by experience, and I was forced to

recognize the plain truth that the only mischievous animal, the only

creature meditating and planning evil on that mountain--excepting of

course the evil incident to the procurement of food--was a man with a

gun. I was the only really dangerous and unnecessarily destructive

animal in the woods, and all the rest were afraid of me.

After a time, because I had no intention of killing Pinto if I should

meet him, I quit carrying a rifle, except when I wanted venison, and

tramped all over the mountain in daylight or in darkness without giving

much thought to possible encounters. True, I carried a revolver, but

that was force of habit mainly, and a six-shooter is company of a sort

to a man in the wilderness even if he does not expect to need it. When

one has "packed a gun" for years, he feels uncomfortable without it;

not because he thinks he has any use for it, but because it has become

a part of his attire and its absence unconsciously frets him and sets

him wondering vaguely if he has lost his suspenders or forgotten to put

on a tie.

That the big Grizzly was not quite so audacious and adventurous as he

was reputed to be was demonstrated by his suspicious avoidance of the

traps while they were new to him, and it became evident that he could

not be inveigled into them even by meat and honey until they should

become familiar objects to him and he should get accustomed to my scent

upon his trails. That I would have caught old Pinto in time there is

no doubt, for eventually he was caught in each of the traps, although

he escaped through the carelessness of the man who baited and set them.

The traps were tight pens, built of large oak logs notched and pinned,

roofed and floored with heavy logs and fitted with falling doors of

four-inch plank. They were stout enough, and when I saw them ten years

later they were sound and fit to hold anything that wears fur, although

old Pinto had clawed all the bark off the logs and left deep furrows in

them.

As a matter of course, all the hunters and mountain men for fifty miles

around knew that I was trying to catch a Grizzly, and some of them

built traps on their own hook, hoping to catch a bear and make a few

dollars. I had encouraged them by promising to pay well for his

trouble anybody who should get a bear in his own trap, or find one in

any of the numerous traps I had built and send me word.

Late in October, I heard that a bear had got into a trap on Gleason

Mountain, and leaving Pinto to his own devices, I went over to look at

the captive. The Mexican acting as jailor did not know me, and I

discovered that Allen Kelly was supposed to be the agent of a

millionaire and an "easy mark," who would pay a fabulous sum for a

bear. The Mexican assured me that he was about to get wealth beyond

the dreams of avarice for that bear from a San Francisco man, meaning

said Kelly, whereupon I congratulated him, disparaged the bear and

turned to go. The Mexican followed me down the trail and began

complaining that the alleged purchaser of the bear was dilatory in

closing the deal with cash. He, Mateo, was aggrieved by this

unbusinesslike behavior, and it would be no more than proper for him to

resent it and teach the man a lesson in commercial manners by selling

the bear to somebody else, even to me, for instance. Mateo's haste to

get that bear off his hands was evident, but the reason for it was not

apparent. Later I understood.

Monarch had the bad luck to get into a trap built by a little syndicate

of which Mateo was a member. Mateo watched the trap, while the others

supplied beef for bait. They were to divide the large sum which they

expected to get from me in case they caught a bear before I did, and

very likely my fired assistant had a contingent interest in the

enterprise. Mateo was the only member of the syndicate on deck when I

arrived, and deeming a bird in his hand worth a whole flock in the

syndicate bush, he made the best bargain he could and left the others

to whistle for dividends. Ten years afterward I met the cattleman who

furnished the capital and the beef, and from his strenuous remarks

about his Mexican partner I inferred that the syndicate had been deeply

disappointed. I also learned for the first time why Mateo was so

anxious for me to take the bear off his hands when the evident original

purpose was to held me up for a good round sum. The hold-up would have

failed, however, because I had spent more than $1,200 and lost five

months' time, was nearly broke, did not represent anybody but myself at

that stage of my bear-catching career, and for all I knew the editor

might have changed his mind about wanting a Grizzly at any price.

Finally I consented to take the bear and struck a bargain, and not

until money had passed and a receipt was to be signed did Mateo know

with whom he was dealing. He paid me the dubious compliment of

muttering that I was "un coyote," and as that animal is the B'rer

Rabbit of Mexican folk lore, I inferred that the excellent Mateo

intended to express admiration for the only evidence of business

capacity to be found in my entire career. That dicker for a bear

stands out as the sole trade I ever made in which I was not

unmistakably and comprehensively "stuck." Mateo was more than repaid

for his trouble, however. He helped me build a box, and get the bear

into it, and I took Monarch to San Francisco and sold him to the editor

of the enterprising paper, who eventually gave him to Golden Gate Park.

The newspaper account of the capture of Monarch was elaborated to suit

the exigencies of enterprising journalism, picturesque features were

introduced where the editorial judgment dictated, and mere facts, such

as the name of the county in which the bear was caught, fell under the

ban of a careless blue pencil and were distorted beyond recognition.

More than one-fourth of Joaquin Miller's "True Bear Stories"' consists

of that newspaper yarn, copied verbatim and without amendment, revision

or verification. The other three-fourths of the book, it is to be

hoped, is at least equally true.

Considering all the frills of fiction that were put into the story to

make it readable, the careless inaccuracies that were edited into it,

and the fact that many persons knew of the preliminary attempts to buy

any old bear and fake a capture, it is not strange that people who

always know the "inside history" of everything that happens, wag their

heads wisely and declare that Monarch was obtained from a bankrupt

circus, or is an ex-dancer of the streets sold to the newspaper by a

hard-up Italian.

But it is incredible that any one who knows a bear from a Berkshire hog

could for an instant mistake Monarch for any variety of tamable bear or

imagine that any man ever had the hardihood to give him dancing lessons.

When Monarch found himself caught in the syndicate trap on Gleason

Mountain, he made furious efforts to escape. He bit and tore at the

logs, hurled his great bulk against the sides and tried to enlarge

every chink that admitted light. He required unremitting attention

with a sharpened stake to prevent him from breaking out.

For a full week the Grizzly raged and refused to touch food that was

thrown to him. Then he became exhausted and the task of securing him

and removing him from the trap was begun. The first thing necessary

was to make a chain fast to one of his fore-legs. That job was begun

at eight o'clock in the morning and finished at six o'clock in the

afternoon. Much time was wasted in trying to work with the chain

between two of the side logs. Whenever the bear stepped into the loop

as it lay upon the floor and the chain was drawn tight around his

fore-leg just above the foot, he pulled it off easily with the other

paw, letting the men who held the chain fall over backward. The feat

was finally accomplished by letting the looped chain down between the

roof logs, so that when the bear stepped into it and it was drawn

sharply upward, it caught him well up toward the shoulder.

Having one leg well anchored, it was comparatively easy to introduce

chains and ropes between the side logs and secure his other legs. He

fought furiously during the whole operation, and chewed the chains

until he splintered his canine teeth to the stubs and spattered the

floor of the trap with bloody froth. It was painful to see the plucky

brute hurting himself uselessly, but it could not be helped, as he

would not give up while he could move limb or jaw.

The next operation was gagging the bear so that he could not bite. The

door of the trap was raised and a billet of wood was held where he

could seize it, which he promptly did. A cord made fast to the stick

was quickly wound around his jaws, with turns around the stick on each

side, and passed back of his ears and around his neck like a bridle.

By that means his jaws were firmly bound to the stick in such a manner

that he could not move them, while his mouth was left open for

breathing.

While one man held the bear's head down by pressing with his whole

weight upon the ends of the gag, another went into the trap and put a

chain collar around the Grizzly's neck, securing it in place with a

light chain attached to the collar at the back, passing down under his

armpits and up to his throat, where it was again made fast. The collar

passed through a ring attached by a swivel to the end of a heavy chain

of Norwegian iron. A stout rope was fastened around the bear's loins

also, and to this another strong chain was attached. This done, the

gag was removed and the Grizzly was ready for his journey down the

mountain.

In the morning he was hauled out of the trap and bound down on a rough

skeleton sled made from a forked limb, very much like the contrivance

called by lumbermen a "go-devil." Great difficulty was encountered in

securing a team of horses that could be induced to haul the bear. The

first two teams were so terrified that but little progress could be

made, but the third team was tractable and the trip down the mountain

to the nearest wagon road was finished in four days.

The bear was released from the "go-devil" and chained to trees every

night; and so long as the camp fire burned brightly he would lie still

and watch it attentively, but when the fire burned low he would get up

and restlessly pace to and fro and tug at the chains, stopping now and

then to seize in his arms the tree to which he was anchored and test

its strength by shaking it. Every morning the same old fight had to be

fought before he could be tied to his sled. He became very expert in

dodging ropes and seizing them when the loops fell over his legs, and

considerable strategic skill was required to lasso his paws and stretch

him out. In the beginning of these contests the Grizzly uttered angry

growls, but soon became silent and fought with dogged persistency,

watching every movement of his foes with alert attention and wasting no

energy in aimless struggles. He soon learned to keep his hind feet

well under him and his body close to the ground, which left only his

head and fore-legs to be defended from the ropes. So adroit and quick

was the bear in the use of his paws that a dozen men could not get a

rope on him while he remained in that posture of defence. But when two

or three men grasped the chain that was around his body and suddenly

threw him on his back, all four of his legs were in the air at once,

the riatas flew from all directions and he was vanquished.

Chained to trees every night

Monarch was pretty well worn out when the wagon road was reached, and

doubtless enjoyed the few days of rest and quiet that were allowed him

while a cage was being built for his further transportation. He made

the remainder of the journey to San Francisco by wagon and railroad,

confined in a box constructed of inch-and-a-half Oregon pine that had

an iron grating at one end. The box was not strong enough to have held

him for five minutes had he attacked it as he attacked the trap and as

he subsequently demolished an iron-lined den, but I put my trust in the

moral influence of the chain around his neck. The Grizzly accepted the

situation resignedly and behaved admirably during the whole trip.

Monarch is the largest bear in captivity and a thoroughbred Californian

Grizzly. No naturalist needs a second glance at him to classify him as

Ursus Horribilis. He stands four feet high at the shoulder, measures

three feet across the chest, 12 inches between the ears and 18 inches

from ear to nose, and his weight is estimated by the best judges at

from 1200 to 1600 pounds. He never has been weighed. In disposition

he is independent and militant. He will fight anything from a crowbar

to a powder magazine, and permit no man to handle him while he can move

a muscle. And yet when he and I were acquainted--I have not seen him

since he was taken to Golden Gate Park--he was not unreasonably

quarrelsome, but preserved an attitude of armed neutrality. He would

accept peace offerings from my hand, taking bits of sugar with care not

to include my fingers, but would tolerate no petting. Within certain

limits he would acknowledge an authority which had been made real to

him by chains and imprisonment, and reluctantly suspend an intended

blow and retreat to a corner when insistently commanded, yet the fires

of rebellion never were extinguished and it would have been foolhardy

to get within effective reach of his paw. To strangers he was

irreconcilable and unapproachable.

Monarch passed three or four years in a steel cell before he was taken

to the Park. He devoted a week or so to trying to get out and testing

every bar and joint of his prison, and when he realized that his

strength was over-matched, he broke down and sobbed. That was the

critical point, and had he not been treated tactfully by Louis Ohnimus,

doubtless the big Grizzly would have died of nervous collapse. A live

fowl was put before him after he had refused food and disdained to

notice efforts to attract his attention, and the old instinct to kill

was aroused in him. His dulled eyes gleamed green, a swift clutching

stroke of the paw secured the fowl. Monarch bolted the dainty morsel,

feathers and all, and his interest in life was renewed with the revival

of his savage propensity to slay.

From that moment he accepted the situation and made the best of it. He

was provided with a bed of shavings, and he soon learned the routine of

his keeper's work in removing the bed. Monarch would not permit the

keeper to remove a single shaving from the cage if a fresh supply was

not in sight. He would gather all the bedding in a pile, lie upon it

and guard every shred jealously, striking and smashing any implement of

wood or iron thrust into the cage to filch his treasure. But when a

sackful of fresh shavings was placed where he could see it, Monarch

voluntarily left his bed, went to another part of the cage and watched

the removal of the pile without interfering.

In intelligence and quickness of comprehension, the Grizzly was

superior to other animals in the zoological garden and compared not

unfavorably with a bright dog. It could not be said of him, as of most

other animals, that man's mastery of him was due to his failure to

realize his own power. He knew his own strength and how to apply it,

and only the superior strength of iron and steel kept him from doing

all the damage of which he was capable.

The lions, for example, were safely kept in cages which they could have

broken with a blow rightly placed. Monarch discovered the weak places

of such a cage within a few hours and wrecked it with swift skill.

When inveigled into a movable cage with a falling door, he turned the

instant the door fell, seized the lower edge and tried to raise it.

When placed in a barred enclosure in the park, he began digging under

the stone foundation of the fence, necessitating the excavation of a

deep trench and the emplacement therein of large boulders to prevent

his escape. Then he tried the aerial route, climbed the twelve foot

iron palings, bent the tops of inch and a half bars and was nearly over

when detected and pushed back.

He remains captive only because it is physically impossible for him to

escape, not because he is in the least unaware of his power or inept in

using it. Apparently he has no illusions concerning man and no respect

for him as a superior being. He has been beaten by superior cunning,

but never conquered, and he gives no parole to refrain from renewing

the contest when opportunity offers.

Mr. Ernest Thompson Seton saw Monarch and sketched him in 1901, and he

said: "I consider him the finest Grizzly I have seen in captivity."

Monarch, The Biggest Bear in Captivity

NOTE.--Without doubt the largest captive grizzly bear in the world, may

be seen in the Golden Gate Park, San Francisco. As to his exact

weight, there is much conjecture. That has not been determined, as the

bear has never been placed on a scale. Good judges estimate it at not

far from twelve hundred pounds. The bear's appearance justifies that

conclusion. Monarch enjoys the enviable distinction of being the

largest captive bear in the world.--N. Y. Tribune, March 8, 1903.

April 24, 2009 06:14PM | Admin Registered: 16 years ago Posts: 17,152 |

CHAPTER III.

CHRONICLES OF CLUBFOOT.

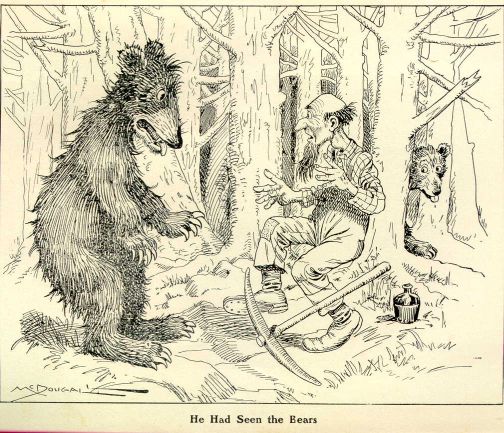

The most famous bear in the world was, is and will continue to be the gigantic Grizzly known variously on the Pacific Slope as "Old Brin," "Clubfoot," and "Reelfoot." He was first introduced to the public by a mining-camp editor named Townsend, who was nicknamed "Truthful James" in a spirit of playful irony. That was in the seventies. Old Erin was described as a bear of monstrous size, brindled coat, ferocious disposition and evil fame among the hunters of the Sierra. He had been caught in a steel trap and partly crippled by the loss of a toe and other mutilation of a front paw, and his clubfooted track was readily recognizable and served to identify him. Old Brin stood at least five feet high at the shoulder, weighed a ton or more and found no difficulty in carrying away a cow. He seemed to be impervious to bullets, and many hunters who took his trail never returned. A few who met him and had the luck to escape furnished the formidable details of his description and spread his fame, with the able assistance of Truthful James and other veracious historians of the California and Nevada press.

For several years the clubfooted Grizzly ranged the Sierra Nevada from Lassen county to Mono, invulnerable, invincible and mysterious, and every old hunter in the mountains had an awesome story to tell of the ferocity and uncanny craft of the beast and of his own miraculous escape from the jaws of the bear after shooting enough lead at him to start a smelter. Old Brin was a never-failing recourse of the country editor when the foreman was insistent for copy, and those who undertook to preserve the fame of his exploits in their files scrupulously respected the rights of his discoverer and never permitted any vain-glorious bear hunter to kill him. As one of the early guardians of this incomparable monster, I can bear witness that it was the unwritten law of the journalistic profession that no serious harm should come to the clubfoot bear and he should invariably triumph over his enemies. It was also understood that a specially interesting episode in the career of Old Brin constituted a pre-emption claim to guardianship, and, if acknowledged by the preceding guardian, the claim could not be jumped so long as it was worked with reasonable diligence.

While Old Brin infested Sierra Valley and vicinity he was my ward, and I regret to say that his conduct was tumultuous and sanguinary in the extreme. I can remember as if it were but yesterday how, one afternoon when Virginia City was deplorably peaceful and local news simply did not exist, Old Brin went on a rampage over toward Sierra Valley and slaughtered two Italian woodchoppers in the most wanton and sensational manner. More than ten years later I met in Truckee an old settler who remembered the painful occurrence well, because the Italians were working for him at the time, and he told me the story to prove that Old Brin had once roamed that part of the mountains. Naturally I was so pleased to learn that my humble effort to keep the local columns of the Virginia Chronicle up to the high standard of frozen truth had not been in vain, that it was with the greatest difficulty I dropped a sympathetic tear when the old settler of Truckee mourned the sad fate of his Italian friends.

If memory be not at fault, it was the episode of the woodchoppers that precipitated the long-cherished design of Virginia City's most noted sportsmen to make a combined effort to secure the pelt of Old Brin and undying glory. About a score of them, heavily armed and provisioned for a month, sallied forth from the Comstock to find and camp upon the trail of the clubfoot bear. They returned without his pelt, but they brought back some picturesque and lurid explanations of their failure and added several chapters to the history of Old Brin.

One of the party was Ned Foster, who never stood to lose on any proposition and never was known to play any game on the square. Being lame, Foster did not have any ambition to meet the big bear, but contented himself with shooting birds for the pot and helping the camp cook. One morning, after all the mighty hunters had gone out on their quest, Foster picked up his shot-gun, jocularly remarked that he guessed he would fetch in a bear, and limped away toward a brushy ridge. Presently the cook heard a shot, followed by yells of alarm, and peering from the tent he saw Foster coming down the slope on a gallop, followed by a monstrous bear. The cook seized a rifle, tried to load it with shot cartridges, and realizing that his agitation made him hopelessly futile, abandoned the attempt to help Foster and scrambled up a tree. From his perch the cook watched with solicitude the progress of Foster and the bear, shouting to Foster excited advice to increase his pace and informing him of gains made by the pursuer.

"Run, Ned! Good Lord, why don't you let yourself out?" yelled the frantic cook, as Foster lost a length on the turn into the home-stretch. "You're not running a lick on God's green earth. The bear's gaining on you every jump, Ned. Turn yourself loose! Ned, you've just got to run to beat that bear!"

Ned went by the tree in a hitch-and-kick gallop, and as he passed he gasped in scornful tones: "You yapping coyote, do you think I'm selling this race!" Perhaps he wasn't, but it looked that way to the man up the tree.

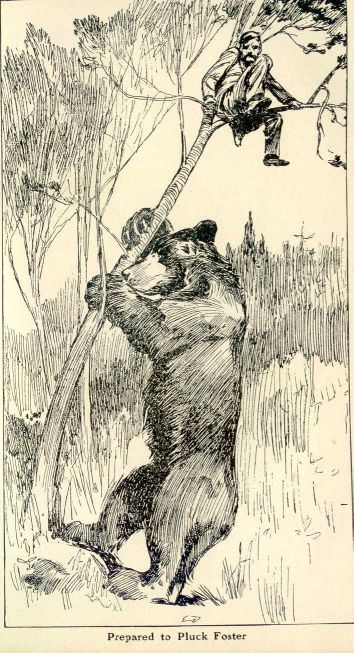

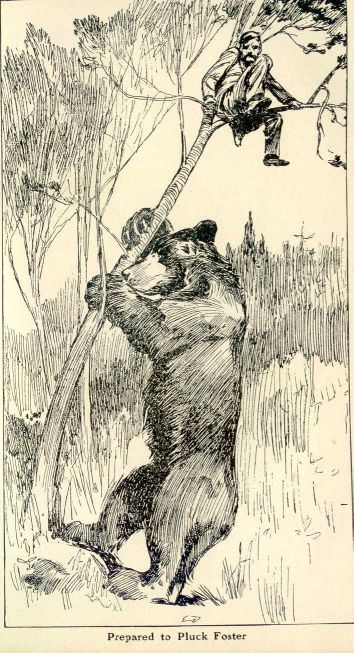

That was the end of the tale as it was told by the Comstockers, who refused to spoil a good climax by gratifying mere idle curiosity about the finish of the race. But Foster was not eaten up by Old Brin—of course his pursuer was the clubfooted bear—and something extraordinary must have happened to save him. An indefinite prolongation of the situation is unthinkable. Wherefore things happened in this wise: Foster's hat fell off, and while the bear was investigating it the man gained a few yards and time enough to climb a stout sapling, growing upon the brink of a cleft in the country rock about a dozen feet wide and twice as deep. The tree was as thick as a man's leg at the base and very tall. Foster climbed well out of reach of the bear, and, perched in a crotch twenty feet above the ground, he felt safe. Old Brin sat down at the foot of the tree, and with head cocked sidewise thoughtfully eyed the man who had affronted him with a charge of small shot. Presently he arose and with his paws grasped the tree ten or twelve feet from the ground, and Foster laughed derisively at the notion of that clumsy beast trying to climb. But Brin had no notion of climbing. Holding his grip, he backed away, and as the tree bent toward him he took a fresh hold higher up, and so, hand over hand, pulled the top of it downward and prepared to pluck Foster or shake him down like a ripe persimmon.

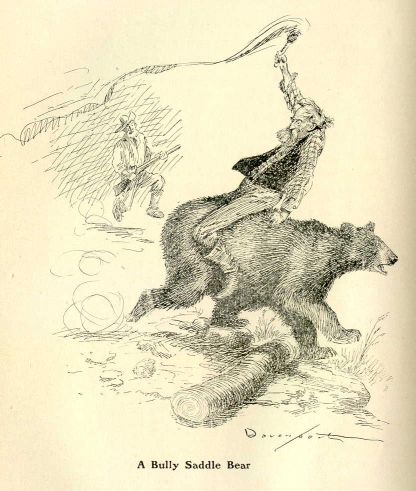

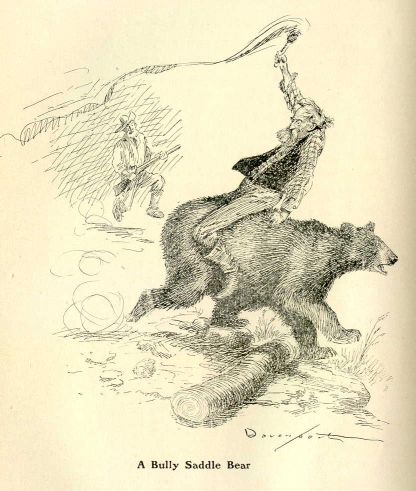

Prepared to Pluck Foster

A part of Foster's habitual attire under all circumstances in warm weather was a long linen duster, and it is a defect of ursine perception to confound a man with his clothes. When the napping skirt of Foster's duster seemed to be within reach, the over-eager bear made a grab for it, and released his grasp of the tree. The backward spring of the tough sapling nearly dislodged the clinging man, but it also gave him an idea, and when the grizzly began a repetition of the manoeuvre, he shifted his position a little higher and to the other side.

Old Brin was not appeased by the shred of linen he had secured, and again began bending the sapling over. This time he had to bend it further to get Foster within reach, but the flapping coat-tail again tempted him too soon, and although he secured most of the skirt, he let go his hold and the tree sprang back like a bended bow. Foster let go his hold too in mid-arc and went sailing through the air and across the ravine, landing in a thicket with a jar that loosened his teeth but broke no bones. He said the Grizzly sat bolt upright and looked at the tree, the ravine and him for five minutes, then cuffed himself soundly on both ears and slunk away in evident humiliation and disgust.

* * * * *

Nothing but Joe Stewart's flawless reputation for veracity could have induced the Comstock to accept the account of Old Erin's visit to camp, which broke up the trip, as it was given by the hunters when they returned. Mr. Stewart made his living at cards and knew no other profession or trade, but his word was as good as a secured note at the bank, his views on ethical questions were considered superior to a bishop's, and all around he was conceded to be a better citizen and an honester man than Nevada had been able to send to the United States Senate. Therefore, as Joe Stewart was one of the party and did not deny that events happened as described by Col. Orndorff, the Comstock never doubted the story of the Blazing Bear. This section of the expedition had a large wall tent and all camp conveniences, including lamps and a five-gallon can of kerosene. They pitched their tent upon the bank of a stream near a deep pool such as trout love in warm weather, and they played the national game every night.

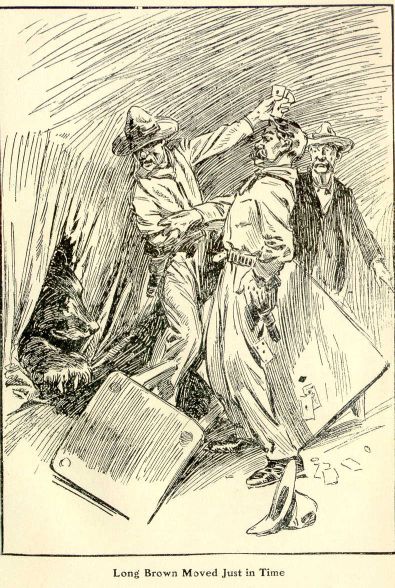

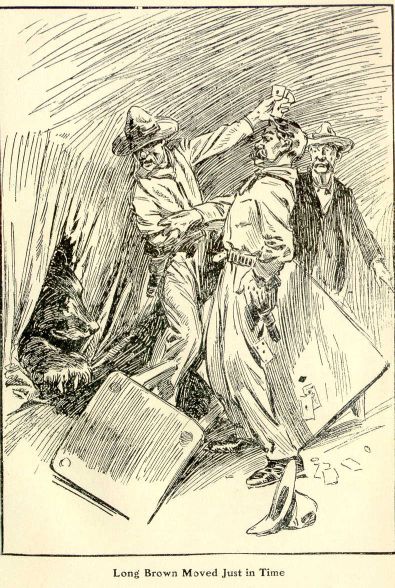

Col. Orndorff had opened an opulent jackpot, and Long Brown was thinking about raising before the draw when he felt a nudge at his elbow as if some one had stumbled against him. He was annoyed and he drove his arm backward violently against the canvas, encountering something solid and eliciting a loud and angry snort. Long Brown moved just in time to escape the sweep of a huge paw, armed with claws like sickles, which rent a great gap in the back of the tent and revealed a gigantic bear still sneezing from the blow on the end of his nose and obviously in a nasty temper.

Long Brown moved just in time

The poker party went out at the front just as Old Brin came in at the back, and Long Brown thoughtfully took the front pole with him, letting the canvas down over the bear and impeding pursuit. The lamps were broken in the fall, and the oil blazed up under the canvas. Col. Orndorff, Mr. Stewart, Bill Gibson, Doughnut Bill and the cook, Noisy Smith, climbed trees before taking time to see how matters were getting arranged in the tent, and Long Brown stopped at the brink of the pool and turned around to see if the bear was following him.

There was complicated trouble in the tent. The bear had tangled himself in the canvas and was blindly tossing it about, rolling himself up in the slack, and audibly complaining of the fire and smoke. The rifles, shot-guns and all but one revolver had been left in the tent, and presently they began to pop. Doughnut Bill, safe in a sycamore, hitched around to the lee side of the trunk and said: "Mr. Brown, I seriously advise that you emulate the judicious example of the other gentlemen in this game and avoid exposing yourself unnecessarily to such promiscuous and irresponsible shooting as that bear is doing."

"That's dead straight," added Col. Orndorff. "Shin up a tree, Brown, or you'll get plunked."